GNR Dundalk 14 July 1966, © George R Mahon, Irish Railway Record Society

The building of the Railways changed everything, even the way we tell the time.

For millennia, people measured time based on the position of the sun; it was noon when the sun reached the highest point in the sky. Sundials were used well in to the Middle Ages. Cities would set their town clock by measuring the position of the sun but it differed from town to town, as the position of the sun changed as you moved east or west. Everyone relied very much on the peal of Cathedral or Church bells to know what time it was.

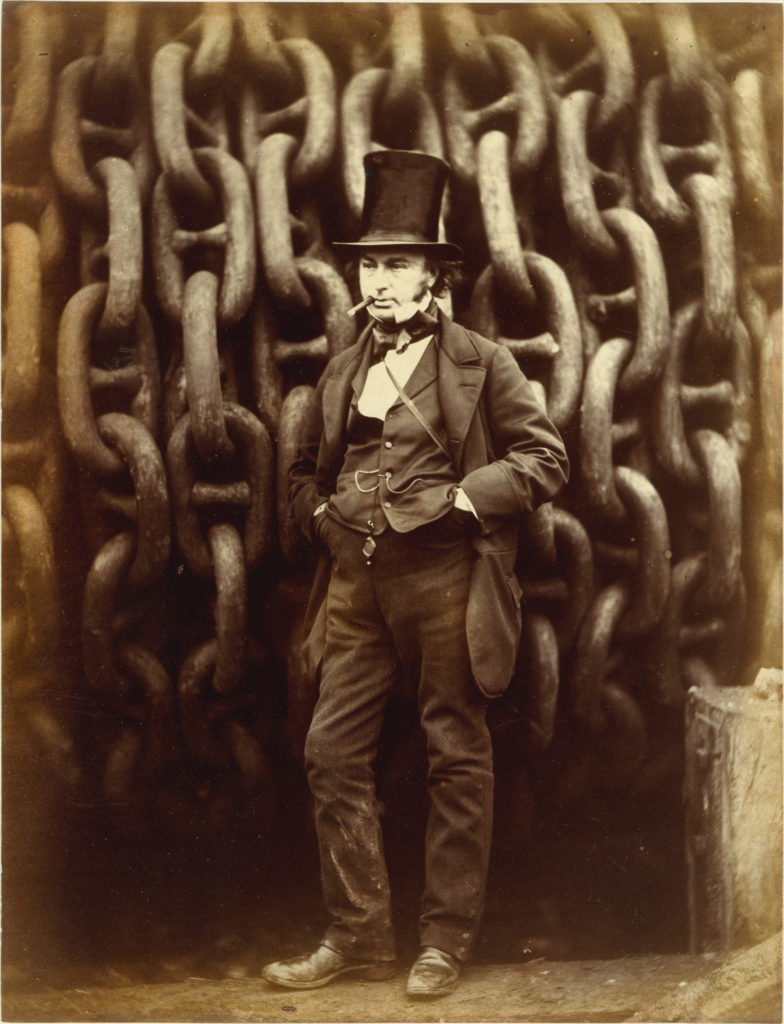

In the 1830’s Isambard Kingdom Brunel was appointed chief engineer of the Great Western Railway (GWR) and he was commissioned to create the fastest railway in the world, connecting Paddington Station London, with Maidenhead, Bath, Bristol, Somerset and eventually South Wales, Devon and Cornwall. The building of the GWR railway is considered an amazing engineering achievement and Brunel himself described as the greatest engineer of the heroic period of 19th century engineering. The rolling stock on his railways included the most powerful locomotives of the day, capable of travelling up to 50 miles per hour.

Small in stature but immense in ambition and legacy, Isambard Kingdom Brunel was famous in Ireland for the planning and execution of the Dublin – Rosslare line. He considered and abandoned the easier inland route that follows the Dublin – Wexford road and opted for the scenic, dramatic coastline which meant cutting through Bray Head. The original line went over many wooden viaducts that ran over the sea, though these were gradually abandoned and the line moved more inland, especially after the Ram’s Scalp bridge accident in 1867 where 2 passengers were killed and 23 injured.

All British towns and cities had their own time. Engineers encountered problems crossing different time zones. Without accurate time keeping railways don’t work. All Brunel’s train time tables noted that “London time was kept at all stations”, which was confusing for passengers and staff.

Before railways a common time between different locations was not important to people’s everyday life. There was no means of transport—or communication over distance—faster than a horse. A few minutes one way or the other between Dublin and Waterford was no problem.

A railway network, however, whose trains could cross the country within a day, needed standard time to ensure that passengers departed on schedule and, importantly, avoid collisions.

The electric telegraph developed in parallel with the railways provided the solution to the problem caused by differing time zones. William Fothergill Cooke developed a system in which electro magnetic signals moved a needle on a dial to point to letters of the alphabet. Telegraph instruments were installed at each station along the route. At the same time in the US Samuel Morse and his colleague Alfred Veil invented a similar transmitter which encoded letters of the alphabet using short and long electrical pulses. His receiver recorded the message on paper in a series of dots and dashes, which became known as Morse Code.

The first clock to display Greenwich Mean Time to the public was the Shepherd Gate Clock. It is a ‘slave’ clock, connected to the Shepherd master clock which was installed at the Royal Observatory in 1852. From that time until 1893, the Shepherd master clock was the heart of Britain’s time system. Its time was sent over the electric telegraph network at railway stations to London, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dublin, Belfast and many other cities. By 1866, time signals were also sent from the clock to Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts via the new transatlantic submarine cable from Valentia Island, Co Kerry.

In terms of the distribution of accurate time into everyday life, it is one of the most important clocks ever made. The first thing you notice about the clock is that it has 24 hours on its face rather than the usual 12. That means at 12 noon the hour hand is pointing straight down rather than straight up.

©Leslie Hyland /IRRS Ciarán Cooney

In 1855 nearly all public authorities, churches and town halls set their clocks to “railway time” displayed on station clocks by station masters as they adjusted them based on the signals from Greenwich. It was very common for people passing by the station to drop inside to check the time. And also considered the ultimate prank by naughty children who would try and change the hands when the station master wasn’t looking!

In 1884 an International Meantime Conference agreed to divide the world into 24 hourly time zones based on the Greenwich meridian. Over the ensuing decades, most countries in the world gradually adopted the principle. Greenwich Meantime was born.

There was some resistance from the church as this now meant their clocks had to be adjusted and they felt they were being bullied by the railways. Eventually most conceded except for the Dean of Exeter Cathedral who resisted and took the railways to court. It dragged on for a year until the arrival of the electric telegraph. But that’s another story!

Due to the political sensitivities of the time, Ireland did not officially adopt Greenwich meantime until October 1916. Before that Dublin mean time was set 25 minutes behind London time.

For over a century, the post office messenger gave the guard of the Irish Mail train at Euston a leather case with a watch which had been set that day at Greenwich observatory to exactly correct GMT. On arrival at Holyhead the watch was shown to an officer on the Kingstown boat which carried the mail and the correct time to Dublin. The watch was then returned to London on another train. This carried on until 1939 with the Irish mail bringing the correct time to Dublin. This practice went back to the time of the mail coaches and showed how railways played their part in uniting the Kingdom and bringing accuracy and modernity to something as basic as having all parts of the country keeping to the same time.

The guard would ring the five minute bell five minutes before the train left but if a passenger was seen racing for the train they would wait.

Interestingly the nursery rhyme Hickory Dickory Dock is thought to have been based on the astronomical clock at Exeter Cathedral. The clock has a small hole in the door below the face for the resident cat to hunt mice.